This text comes from our book, Lands of Hope and Promise.

In his latest transformation—into a conservative dictator—Santa Anna had decided that he had to do something about Texas. Liberalism was triumphant there. The laws were not being observed. Anglo-Americans, like a barbarian horde (that’s how the Mexicans saw them), were crossing the border illegally. To remedy the situation, Santa Anna sent an army under General Martín Perfecto de Cos north to enforce obedience to the law. Learning of Santa Anna’s plans from Lorenzo de Zavala, who had gone north to warn the Texians of the general’s approach, Stephen Austin, now released from imprisonment, called on Texians to take up arms. Sam Houston was made general of a Texian army. In early October 1835, Cos arrived with 1,200 troops at San Antonio de Bexár; he fortified the city, including the old Franciscan mission church, San Antonio de Valero, known as the Alamo. Throughout October and November, armed Texians and some Tejanos arrived at San Antonio de Béxar and lay siege to the city.

On December 4, Texian colonel Benjamin R. Milam gathered the Texian army and, the next day, assaulted Cos’ position in the city. For five days battle raged as the Texians pushed their way into San Antonio. Finally, on December 10, Cos surrendered. The Texians occupied the city and fortified the Alamo.

Santa Anna had had second thoughts after he sent Cos to Texas; he decided that he wanted the glory of crushing the Texian revolution for himself. Establishing his headquarters at San Luis Potosí, about 260 miles northwest of Mexico City, Santa Anna impressed Indians and other “recruits”—men who had known nothing of army service before—until he had built up a sizable force. The government had no money to finance an army, so Santa Anna took out loans at ruinous interest rates. He manufactured munitions and requisitioned horses and carts. Whipping the men into some semblance of discipline, Santa Anna drove them north across the deserts of Coahuila, toward Texas.

Those who know nothing of deserts may not understand how bitterly cold they can be in winter. Both men and animals in Santa Anna’s army suffered terribly from cold, hunger, and disease. Still, the ever implacable Hero of Tampico forced them on until, having left behind many dead, the Mexican army stood, half starved, outside the walls of the Alamo.

Meanwhile, the Texians at the Alamo were quarreling over how to conduct the war and changed their commander almost daily. The garrison, numbering only about 150 men, eventually fell to the command of 27-year-old William Barrett Travis. Born in South Carolina, Travis had spent many years in Alabama, where he had become a lawyer and a Mason. Abandoning his wife, son, and unborn daughter, Travis went to Texas in 1831, where he set up a law practice and joined those who were conspiring for independence from Mexico. Houston had ordered Travis to evacuate the Alamo, but he was determined to remain. He ordered the fortification of the mission to prepare for the assault he knew would come.

Defending the Alamo with Travis were both Texians and Tejanos—among them the frontiersman David Crockett and James Bowie, famous for his long hunting knife. Bowie had come to Texas in 1830. Before that, both he and his brother, Rezin (pronounced like reason), had engaged in illegal slave smuggling in Louisiana (the pirate, Jean Lafitte, was their supplier) and in land speculation. Shortly after coming to Texas, James Bowie was baptized a Catholic and married into a prominent San Antonio family. Over the next few years he gambled, engaged in land speculation, and earned the ill will of Stephen Austin, who thought him a charlatan. Bowie, though, had distinguished himself as a brave leader in the battle of Béxar against General Cos.

David Crockett was a late-comer to Texas, having arrived at the lag end of 1835. Already a legendary frontiersman, Crockett had fought in the Creek Wars and had served in Congress as a representative from Tennessee, where he distinguished himself as an opponent of Jackson’s Indian removal policy. When in 1835 he lost his congressional seat to a Jackson man with a peg-leg, Crockett told friends, “Since you have chosen to elect a man with a timber toe to succeed me, you may all go to hell and I will go to Texas.” And to Texas he went, arriving just in time to join Colonel Travis at the Alamo.

On February 23, 1836, Santa Anna with 3,000 ragged troops laid siege to the 150 defenders of the Alamo. For two weeks, Travis refused to surrender. Finally, in the early hours of March 6, Santa Anna ordered the trumpeter to sound the deguello—the ancient signal used in the Spanish wars against the Moors, signifying “take no prisoners.” The assault began. Travis died early on in the battle, with a single bullet through the head. Bowie, whom sickness had confined to bed, had his skull shattered by six bullets. Almost all the defenders died within a few hours, and Santa Anna commanded that those who had been captured must be shot. It is uncertain what happened to David Crockett. One account by an eyewitness, the Mexican officer José Enrique de la Peña, says that Crockett was among the captured. De la Peña continues that, after his plea for his life was refused, Crockett was bayoneted and then shot. He died bravely, without complaint.

A few days before the Alamo massacre, a convention of Texians had met at Washington-on-the-Brazos, 200 miles east of San Antonio de Béxar, and proclaimed Texas an independent republic. They appointed David Burnet provisional president, and as vice president they chose Lorenzo de Zavala, the former governor of the state of México. Sam Houston, hearing that Santa Anna’s army had turned east and was terrorizing the population as it advanced, ordered a general retreat. The entire population of Texas was in flight before the victorious Santa Anna.

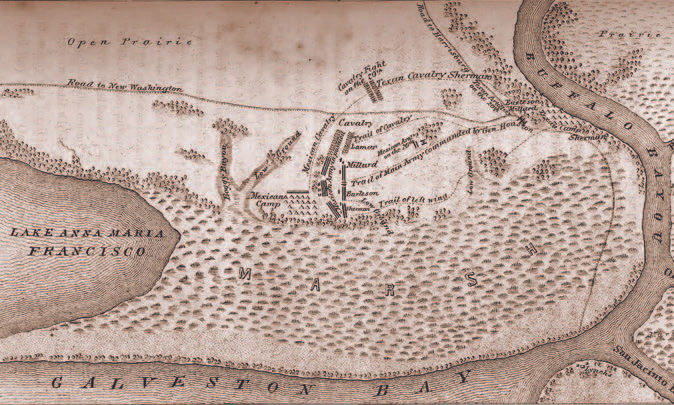

The grand conqueror, hearing that the provisional Texas government had removed to Harrisburg at the mouth of the San Jacinto River, thither led his force to bag Houston’s army and the rebellious government at once. Santa Anna met Houston and his small army at Lynchburg Ferry on the San Jacinto, and a face-off ensued between the two armies. A day passed, and no action. Santa Anna, whose tent sat on a small rise not far from the enemy’s lines, lay down to take a conqueror’s well-earned siesta. He had posted no sentries or pickets, so the first notice he received of Houston’s attack was the impassioned shout, “Remember the Alamo!” He had barely time to escape. Houston’s small force, with a loss of only three dead and 18 wounded, destroyed the Mexican army—400 died, 200 were wounded, and 730 were taken prisoner. Next day, the Texians captured Santa Anna; they found him hiding in high grass, clad in a blue shirt, white trousers, and red slippers.

The Battle of San Jacinto ended the war. To assure his release, the conquered Napoleon promised to recognize the independence of Texas. Santa Anna did not return home directly but went on to Washington where he met with President Jackson. After a cordial meeting, Jackson sent Santa Anna home by ship. Arriving in Mexico, Santa Anna retired to Manga de Clavo, his loss of Texas having assured his loss of the presidency. Anastasio Bustamante succeeded Santa Anna and Barragán as president.

Though the Mexican government refused to acknowledge Texas’ independence, it did nothing to win back the rebellious territory. Texas remained an independent republic.

Looking for your chance to spin and win every day? Take advantage of our Daily Free Spins and enjoy the excitement of winning without spending a dime! Every day is a new opportunity to land huge rewards — no purchase required. Spin the wheel, unlock your fortune, and keep coming back to try your luck!